History of Honey Bees in America

Honey Bees Across America

By Brenda Kellar

The creation of the United States can be found in the footsteps of the honey bee (Apis mellifera L.). Brought to the east coast of North America in 1622 it would be 231 years before the honey bee reached the west coast. Disease, hostile competitors, harsh climates, and geographical barriers blocked the advance of honey bee and human alike.

Their greatest advantage was each other. The honey bee provided honey, wax, and propolis for human consumption and market, they pollinated the European seeds and saplings that the immigrants brought with them, and they changed the environment (many times in advance of the human immigrants) making it more acceptable to the imported livestock by helping to spread white clover and other English grasses. Christopher Gist wrote in 1751 when near the present site of Circleville “all the way from Licking Creek to this Place is fine rich level Land, with large Meadows, Clover Bottoms & spacious Plains covered with Wild Rye” and west of the Alleghenies “the first arrivals found white clover and Kentucky bluegrass” (Bidwell and Falconer 1925:157). In return the humans provided shelter, encouraged swarming, planted large tracts of plants that are highly utilized by honey bees, and aided the honey bees’ travels over barriers like treeless plains and mountain ranges.

Historical archaeology, with its interdisciplinary approach and incorporation of historic materials with artifacts, is the discipline most suited to discovering the long-term processes that produce changes in both culture and the environment. Honey bees, and I could argue all insect species, leave traces of their impact on the environment and on human cultures that historic archaeology is uniquely designed to uncover.

Changes in plant species populations can be traced through the pollen left in the soil as well as in the diaries and letters colonists and travelers have left behind. The fact that the United States was founded on an agricultural economy that was principally based on the crops brought to North America and which the honey bees were familiar with, and principle pollinators of, is another indication of the influence the honey bee had on the development of the United States.

Pieces of honey bee anatomy can also be found in the soil. Those most likely to survive deposition are the thicker, tougher pieces of chitin like mandibles and stingers. Under some circumstances (anaerobic environments are one example) the more delicate pieces like wings would probably be found. As these soils can often be dated through stratigraphy, magnetic changes, or association the honey bees’ physical remains could also be dated.

The honey bees left more than just their bodies for us to discover. They left behind an entire economic industry with all of its attendant tools, advertising, and monetary records. Human cultures for thousands of years have used the honey bee and her products as symbols for industry, social structure, cleanliness, holiness, chastity, and much more. These symbols can be found in all forms of material culture produced by human populations. Native American languages, diet, art, technologies, and oral histories also changed with the arrival of the honey bee. John Eliot, who in 1661 translated the New Testament into a Native American language and in 1663 completed the entire Bible, both of which he published in Massachusetts, found there was no Native American word for wax or honey and claimed that the Indians used the term ‘White Man’s fly’ (Pellett 1938:2).

The only evidence we have of the initial importation of honey bees to North America is a letter written December 5, 1621 by the Council of the Virginia Company in London and addressed to the Governor and Council in Virginia, “Wee haue by this Shipp and the Discouerie sent you diurs [divers] sortes of seedes, and fruit trees, as also Pidgeons, Connies, Peacockes Maistiues [Mastiffs], and Beehives, as you shall by the invoice pceiue [perceive]; the preservation & encrease whereof we respond vnto you…” (Goodwin 1956; Kingsbury 1906:532). The Discovery (60 tons, Thomas Jones, captain, and twenty persons) left England November 1621 and arrived in Virginia March 1622 (Langford Ship Information; Brown 1898:469-470). The other ship described only as “this shipp” could have been either the Bona Nova (200 tons, John Huddleston, master, and fifty persons) or the Hopewell (60 tons, Thomas Smith, master, and twenty persons), also known as the Great Hopewell. The Bona Nova was a month behind and arrived at Jamestown in April (Langford Ship Information). This was the Hopewell’s first voyage to Virginia and there is no record of the date of its arrival (Langford Ship Information), although Brown claims it arrived at Jamestown within 24 days of the Good Friday March 22, 1622 massacre (Brown 1898:469).

Historical documentary sources tell us that from Jamestown the honey bees multiplied and spread out. It would be another 16 years before the next successful shipment of honey bees made it to North America (Free 1982:116; Ransome 1937:260). However, the feral honey bee population boomed and by the mid 17th century honey bee hunting or ‘lining’[1] was a popular activity and would continue to be so well into the 20th century.

May 10, 1632 Providence Rhode Island asked for honey bees to be sent from the main (Sainsbury 1964:147-148) but this request was not fulfilled. The second import of honey bees was in 1638 to Massachusetts (Free 1982:116; Ransome 1937:260). Two years later Newbury, Massachusetts initiated a municipal apiary (Adams 1921:277; Crane 1975:475; Pellett 1938:3). This was intended to be a combination educational experiment station and welfare program. Eels, from a town now called Hingham, was put in charge of the apiary, which was placed on a farm rented by John Davis (Adams 1921:277; Pellett 1938:3). By 1643 Eels was living with John Davis. For some reason Eels ran away, but he was caught, jailed, and set to constructing hives (Adams 1921:277). The apiary was a failure and Eels became the town’s first pauper (Adams 1921:277; Crane 1975:475; Pellett 1938:4).

The first 17th century Virginia apiary that I could find evidence of was owned by George Pelton, a.k.a. George Strayton. It was impressive enough that one of his neighbors wrote to England about the apiary. March 1648:

“For bees there is in the country which thrive and prosper very well there; one Mr. George Pelton, alias, Strayton, a ancient planter of twenty-five years’ standing that had store of them, he made thirty pounds a year profit of them; but by misfortune his house was burnt down, and many of his hives perished, he makes excellent good metheglin, a pleasant and strong drink, and it serves him and his family for good liquor: If men would endeavour to increase this kind of creature, there would be here in a short time abundance of wax and honey, for there is all the country over delicate food for bees, and there is also bees naturally in the land, though we account not of them” [Goodwin 1956; Maxwell 1849:76; Riley 1956].

By the last quarter of the 17th century the honey bee had spread northward into all areas of New England although the “Bees seem to have been more common in the Middle Colonies than in New England” (Bidwell and Falconer 1925: 32). In Pennsylvania, Thomas wrote, the Swedish immigrants “often get great store of them [honey bees] in the woods where they are free for any Body. Honey (and choice too) is sold in the Capital City for Five Pence per Pound. Wax is also plentiful, cheap, and a considerable Commerce’” (Bidwell and Falconer 1925: 32).

In the 18th century the interest in beekeeping continued to expand and five American bee books were published (Mason: 34-649). Previously all such single subject books were published in England or Europe.

James Tew claims there were two distinct bee industry epochs:

(1) 1700-1800 when honey bee colonies are wild, and honey hunters occasionally rob honey.

(2) 1800s when honey bees are kept as farm animals to provide honey for personal use

Although I agree with Bidwell and Falconer (1925: 69) when they say that there were “two sharply contrasted types of farming and of rural life: (a) pioneering, the agriculture of the new settlements on the frontier, and (b) the agriculture of the older communities along the seacoast and in the river valleys” in New England and the Middle Colonies of the 18th century, they nor I can agree with Tew’s claim. “Honey was another substitute for cane sugar, bees being considered an important adjunct of every well-managed [18th century] farm” (Bidwell and Falconer 1925: 127).

The lack of information about honey bees and apiaries in the documentary record for the 18th century gives the impression that honey bee populations were mostly feral and that their products were supplemental to the settlers’ diet. This is disputed by the fact that beeswax was an important 18th century Virginia export. Sir William Gooch, governor of Virginia from 1727 – 1749, described Virginia’s commodities, which included beeswax (Bruce 1896:118). In a 1743 report to the Board of Trade, Governor Gooch stated that the wax was exported to Portugal and the Island of Madeira (Chandler 1925:238). This pattern held into the second half of the 18thcentury and in Mair’s Book-keeping (1760) the products of Virginia and Maryland[2] included beeswax. All the products were “generally export, in small sloops of their own, to the West India Islands particularly to Barbadoes, Antigua and St. Christophers; and in return, bring home rum, sugar, molasses, and cash, being mostly Spainish coins” (Tyler 1966:I:215, XIV:87).

The total amount of beeswax exported from Virginia in 1730 (just over one hundred years since the first import of honey bees to North America) was 156 quintals, equal to 156,000 kilograms, or about 343,900 pounds (Pryor 1983:20). Beers (1804:29) claimed that the average managed hive yielded 20 pounds of honey and 2 pounds of wax. If this is correct then there had to be 171,950 hives harvested that year just for export purposes. There would have been many more hives harvested for domestic use. This booming Virginia beeswax export continued and in 1739 five tons of beeswax @ 12d = £12,500 were shipped out (Chandler 1925:240) and in 1743 four tons valued at £400 were exported (Chandler 1925:238; Pryor 1983:20). Even with this volume of wax production the records from 1747 to 1758 for Prince George’s County, Maryland, only mention bees in 7% of large estates (over £200). There was no mention of honey bees for the middle and lower class farms (Pryor 1983:6).

There are extensive legal records for Augusta Co, VA from the years 1745 to 1826. According to these records the honey bees themselves were valuable. Out of 748 inventories 37 included honey bees and the average price of those honey bees was 0-5-3 per swarm/hive. This was similar to the value of a sheep (0-6-0) or a calf (0-5-0) and more than a hog (0-3-2) from the same set of inventory records (Beekeeping Bibliography).

It was only with the help of humans that the honey bees managed to cross the last geographic barrier – the Rocky Mountains. Some immigrants transported them overland while others shipped the honey bees around the horn of South America.

There are several instances of people commenting on the lack of honey bees in the Oregon Territory and an interesting tale of an effort to bring honey bees west across the Applegate Trail in 1846. A settler planning to travel on the Applegate trail was offered $500 for the successful delivery of just one hive of live honey bees, so he packed two hoping that one would survive the trip. The honey bees died when the cold and snow of winter arrived before the wagons made it across the mountains (Williams 1975:33). I believe that their death was probably caused by dysentery, starvation, or a lack of ventilation in the hives rather than because of the cold.

Although some claim that Tabitha ‘Grandma’ Brown, who owned and ran a school and orphanage in Forest Grove, Oregon, had a honey bee tree at the school in 1849 (Williams 1975:34) the first evidence I could find of honey bees in Oregon was the August 1, 1854 Oregon Statesman, which included a story about John Davenport of Marion county who brought home a hive of honey bees from back east. These were considered the first in the area. Unfortunately, it was later reported that this first hive of honey bees did not do well (Williams 1975:34).

Honey bees came to California almost simultaneously with the Oregon honey bees. There is just no support for the story that the honey bees brought to Sitka, Alaska in 1809 by Russian missionaries and traders were carried down to Fort Ross, California in 1812 (Essig 1931:265-266; Free 1982:117). Much more likely is the story told in an 1860 letter from F. G. Appleton, a San Jose apiarist, that says the first honey bees in Californiaarrived in March 1853. There were 12 swarms purchased in Panama, which were carried across the “Isthmus and thence by water to San Francisco” (Essig 1931:268). Only one hive survived the trip and that hive was taken to San José where it produced three successful swarms that first year.

According to documentary evidence it took the honey bee more than 200 years to cross the continental United States. At this time documentary evidence is all we have and this can present some problems. Documents are produced by humans who are constrained by their knowledge of the subject and their ability to communicate through writing. It may be that honey bees were in some of the areas well before someone thought it important enough to comment on or before anyone was aware of their presence.

By incorporating historic archaeology and entomology we can uncover the path of the honey bee as it crossed the future United States. Verifying the documentary record in some instances and probably discovering new information in others. This will help us understand the interactions between the environment and humans, giving us a way to look at how human choices affect not only human systems but ecosystems as well.

Works Cited

Adams, George W. “Some Early Beekeeping History.” American Bee Journal. July 1921.

The Association for Preservation of Virginia Antiquities. Jamestown Rediscovery: The Discovery. http://www.apva.org/

Beekeeping Bibliography last print date 2/13/93 last revision date 6/21/92. Williamsburg, VA: Rockefeller library.

Beers, Andrew. “A Short History of Bees. In Two Parts. 1803.” Romyen’s Johnstown Calendar: or the Montgomery County Almanac for…1804. Johnstown NY: Romyen, 1804.

Bidwell, Percy Wells and John I. Falconer. History of Agriculture in the Northern United States 1620-1860. Washington: Carnegies Institution of Washington, 1925.

Brown, Alexander. The First Republic in America. Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin and company, 1898.

Bruce, Philip A., Ed. The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography Vol III for the year ending June 1896. Richmond: The Virginia Historical Society, 1896.

Chandler, J. A. C. & E. G. Swem Eds. William and Mary College Quarterly Vol V series 2. Williamsburg: William & Mary College, 1925.

Crane, Eva. Honey A Comprehensive Survey. London: William Heinemann Ltd. 1975.

Education Place. Map of the United States 1860. www.eduplace.com

Essig, E. O. A History of Entomology. New York: The Macmillan Co. 1931.

Free, John B. Bees and Mankind. London: George Allen and Unwin Ltd., 1982.

Goodwin, Mary. Response to request for info on beehives and bee culture Jan 26, 1956. Williamsburg, VA: Rockefeller, John D. Jr. Library.

Kingsbury, Susan Myra. The Records of the Virginia Company of London The Court Book, From the Manuscript in the Library of Congress 1619 – 1622 Vol 1 and 2. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1906.

Langford, Thomas. “Ships to America – Virginia 1622.” American Plantations and Colonies. http://english-america.com/places/va162.html#1622

Mason, Philip A. American Bee Books: An Annotated Bibliography of Books on Bees and Beekeeping From 1492 to 1992 Two volumes. Cornell University Dissertation, January 1998.

Maxwell, William Ed. The Virginia Historical Register and Literary advertiser Vol II for the year 1849. Richmond: Macfarlane and Fergusson, 1849.

Microsoft Office Online. Microsoft Office Clip Art and Media Homepage. http://office.microsoft.com/clipart/default.aspx?lc=en-us

Miner, T. B. The American Bee Keeper’s Manual; Being a Practical Treatise on the History and Domestic Economy of the Honey-Bee Embracing a Full Illustration of the Whole Subject, with the Most Approved Methods of Managing this Insect Through Every Branch of its Culture, The Result of Many Years’ Experience. New York: C.M. Saxton and Co, Agricultural Book Publishers, 1857.

Pellett, Frank Chapman. History of American Beekeeping. Iowa: Collegiate Press, Inc., 1938.

Pryor, Elizabeth B. Honey, Maple Sugar and Other Farm Produced Sweetners in the Colonial Chesapeake. Accokeek, Maryland: The National Colonial Farm Research Report, 1983.

Ransome, Hilda M. The Sacred Bee in ancient times and folklore. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co, 1937.

Riley, E. M. Response to Mr. Campioli’s request for information on bees Jan 19, 1956. Williamsburg, VA: Rockefeller, John D. Jr. Library.

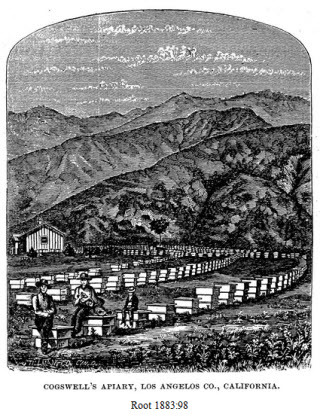

Root, A. I. The ABC of Bee Culture: A Cyclopedia of Everything Pertaining to the Care of the Honey Bee: Bees, Honey, Hives, Implements, Honey Plants, &c., &c.: Compiled From Facts Gleaned From the Experience of Thousands of Beekeepers, All Over Our Land, And Afterward Verified By Practical Work in Our Own Apiary. Medina, Ohio: A. I. Root, 1883.

Sainsbury, W. Noel Ed. Calendar of State Papers, Colonial Series, 1574 – 1660. London: Kraus Reprint Ltd., 1964.

Society for Historic Archaeology (SHA). http://www.sha.org/About/sha_what.htm

Spencer, Maryellen. Food in Seventeenth-Century Tidewater Virginia: A Method for Studying Historical Cuisines. Ann Arbor: UMI Dissertation Services, 2000.

Tew, James, E. “Bee Culture’s Beeyard” Bee Culture Magazine. February 2001.

Tyler, Lyon G Ed. William and Mary College Quarterly Historical Papers Vol I 1892-1893. New York: Kraus Reprint Corporation, 1966.

Tyler, Lyon G Ed. William and Mary College Quarterly Vol XIV 1905-1906. New York: Kraus Reprint Corporation, 1966.

Williams, Catherine. “Bringing Honey to the Land of Milk and Honey – Beekeeping in the Oregon Territory.” The American West “The Magazine of Western History.” Vol XII No 1 January 1975

______________________________________________________________________________

[1] Ransome suggested this was where the term ‘beeline’ came from (Ransome 1937:272).

[2] “The produce or commodities of the growth of Virginia and Maryland are pitch, tar, turpentine, plank, clapboard and barrel staves, shingles, wheat flour, biscuit, Indian corn, beef, pork, fallow, wax, butter and liye stock, such as hogs, geese and turkeys” (Tyler 1966:1:215, XIV:87).

[Note from LACBA: We'd like to thank Brenda Kellar for granting permission to the Los Angeles County Beekeepers Association to utilize Honey Bees Across America on our website.)